The black ash tree (Wisqoq / Frêne noir / Uinnseann duhb) is a long-lived, slow-growing hardwood native to the Wabanaki-Acadian forest and found throughout the Dawnlands as well as interior Eastern North America. It has significant cultural value as a source of flexible wood strips, used by the Mi’kmaq and many other first nations to create snowshoe frames, canoe ribs, baskets, and barrel hoops, as well as medicines, and was an important part of indigenous and rural settler economies when it was more common in Eastern forests. Wisqoq is known as Wikp in the Wolastoqiyik-Passamaquoddy language, Maahlakws in Abenaki, and Éhsa in Kanien’kéha, just to name a few languages of neighbouring nations, who all value this important species!

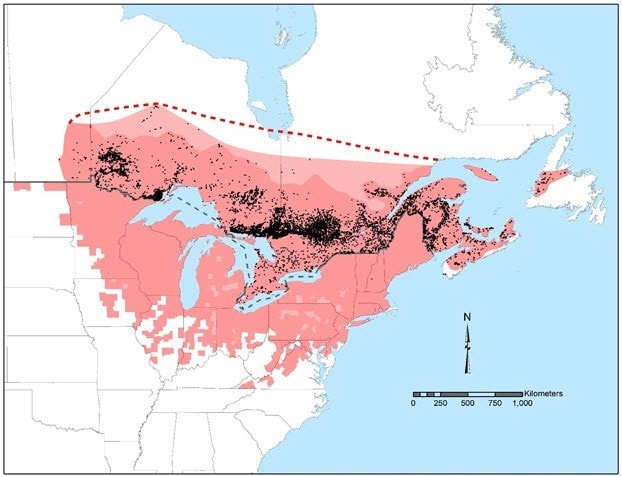

Wisqoq is found from Newfoundland westward to Cree, Metis, and Anishinabek territories, and Southward from the Midwest to Lenape Confederation and Susquenhannock lands also known as New Jersey, Delaware, and Maryland. A little over half of the global range of the black ash tree is found in Canada. It occurs mainly in swamps, treed floodplains, and fens, as well as moist upland forests and may grow either in dense, near-uniform stands or singly inside the boundaries of small disturbed areas, such as the wind-thrown openings characteristic of the Wabanaki-Acadian forest. In especially wet forests, it may act as a climax species, dominating the canopy and regulating local hydrology by taking up water and maintaining drier habitat for other, less wet-tolerant species.

Wisqoq was designated as Threatened under the Canadian Species At Risk Act (COSEWIC) in 2018, prompting the creation of a federal status report. It was previously listed as Threatened in Nova Scotia, in 2013, which resulted in the creation of a provincial Recovery Plan, in 2015. In 2019, naturalists like you came together to advocate for the inclusion of Core Habitat in this plan, a legal requirement under the provincial Endangered Species Act but one which the province never completed, resulting in the 2020 judicial review where several species at risk won against the province at court.

Much of our understanding of Wisqoq’s global population trends comes from incomplete forestry surveys, which suggest a gradual to extreme decline over most of the species’ range. Local trends are not well understood, though the tree’s rarity in the Maritimes has resulted in the generation of more specific occurrence data than in some other jurisdictions, revealing ash hotspots in Caledonia, Wentworth, and Shubenacadie. Conversion of forests and wetlands to other land uses since European settlement over the nineteenth and twentieth centuries is widely thought to be the main factor behind the significant declines, at least in the Great Lakes region, and this is likely part of the story in the Dawnlands as well. However, the continued decline in Nova Scotia since this time is less well understood. The entire provincial population is estimated at approximately 1,000 individuals, mostly made up of young saplings and only a few mature trees. These trees, together, make up less than 1% of the estimated national population. Habitat is still declining across the country, but continued habitat loss is thought to be significantly reduced compared to 19th and early 20th century losses, and it doesn’t explain the entirety of the decline in ash numbers today.

Wisqoq has likely never been common in the far southwest or along the Atlantic coast of Nova Scotia, where soils are strongly acidic and wet forests are more likely to be dominated by spruce and fir species. However, Wisqoq was likely common throughout the rest of the province, both as dense ash-dominated stands and as less common single-tree occurrences inside other mixed forests, before the early 1800s. In Kings County New Brunswick, black ash has reportedly declined in frequency of occurrence (the number of trees found within a certain area) from 6.5% in the early 1800s to less than 1% in 1993 (Loo and Ives 2003). In Nova Scotia, provincial forest inventory data suggest a population decline of 45% or more since the 1950s (COSEWIC, 2018). Mi’kmaq basket makers, consulted as part of the federal status report creation, agreed that Black Ash is rare in Nova Scotia but could not confirm that the species had declined over time. Though ash has traditionally been used in basketry in Nova Scotia, Mi’kmaq artists in this area are also known to have brought materials in from Quebec, New Brunswick, and Maine for at least the last 80 years.

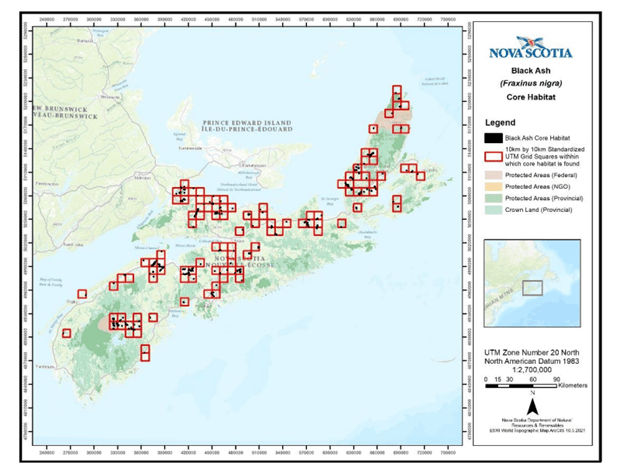

The Nova Scotia government should have released a definition of Core Habitat for black ash at the same time it released the 2015 Recovery Plan, as required by the Nova Scotia Endangered Species Act. Core Habitat is the specific area essential for the long-term survival and recovery of endangered or threatened species. Given the uncertainty in Wisqoq’s distribution and abundance in Nova Scotia, the province may have assumed there was not enough information available to define this feature even though excluding this measure would constitute a violation of provincial legislation (in fact, this was the reason given during the province’s defence at the judicial review.) As a result, and after years of waiting for other species to receive their legally-required protections, Wisqoq eventually became of the six species featured in the Bancroft vs Lands and Forestry judicial review that naturalists like you helped us prepare for in 2020. Justice Brothers sided with the ash, the province was ordered to catch up on its legal duties to species at risk, and an amendment to the Recovery Plan was released in the fall of 2021 that finally defined Core Habitat as the area of all known black ash occurrences plus a buffer of 100-200m, depending on the depth to the water table. As currently defined, these ~1,000 known black ash trees now fall into 112, 10km2 areas, many clumped together in northern and western Cape Breton, the North Shore, the Annapolis Valley, Molega Lake to Kejimkujik National Park and Historic Site, and along the Shubenacadie River. Though neither the Status Report, Recovery Plan, or Core Habitat amendment specify how the Nova Scotia government should go about achieving the conservation of these areas, they do state that this Core Habitat should be “protected.” The Core Habitat addendum also stipulates that the current definition should be updated as new information (and presumably confirmation of new occurrences) becomes available.

Threats to Black Ash

European settlement in Nova Scotia is estimated to have resulted in the loss of at least 80% of historic saltmarshes and an unknown percentage of freshwater wetlands, but this loss is largely spread out across our region rather than concentrated in one area, as is more the case in Southern Ontario. As a result, and in part due to a relatively small human population and the tree’s naturally wide distribution, there are likely still pockets of intact or regenerating wet forest in much of Nova Scotia that may harbour black ash or provide sites for reestablishment efforts. As such, the remaining black ash population in Nova Scotia may be more evenly distributed than in other areas, even if the trees are more spatially spread out.

Many of these wet sites are not formally protected though, occurring either on public lands but missing from the province’s wetland inventory or not meeting requirements for protection under the Wetland Conservation Policy, or occurring on private lands but unknown/unvalued by the landowner. Even trees located within the newly defined Core Habitat areas are not necessarily offered any additional protections because of their location within the Core Habitat grid. The province estimates that just 10% of the area identified as Core Habitat for Wisqoq is currently protected, either through the National Parks system, provincial Parks and Protected Areas Plan, or as private conservation lands administered by land trusts. 78% of Core Habitat sits on private lands (COSEWIC, 2018).

Wetlands under 2ha may be developed in Nova Scotia without an Environmental Assessment and wetlands under 100sq m may be developed without any kind of alteration approval (NSDNR, 2019). Small wetlands, like those that harbour Wisqoq, are not subject to watercourse regulations and therefore may be harvested with the rest of the surrounding forest, meaning that many ash were likely lost to the rise of clearcut forestry in the 20th century before listing as a species at risk. Despite listing as a species at risk today, ash may continue to fall victim to unsustainable harvest practices, as an indirect result of changed hydrology in forests experiencing large biomass removals.

The introduced emerald ash borer (EAB), first discovered in Ontario in 2002, is likely the most important driver behind black ash population trends today. The beetle has already decimated stands in the Midwest and central Canada and is expected to result in an overall mortality rate of 90%, with 73% of the Canadian black ash population affected within just one generation (or 60 years). It was found in the Maritimes in 2018. Emerald ash borer larvae feed on the inner bark and sapwood of the tree, girdling and killing individuals quickly after infection. Cold can prevent the spread of the beetle but warmer temperatures expected under continued climate change will likely reduce if not eliminate this protection across most of the tree’s range. Biological controls for EAB were introduced in Ontario and Quebec in 2015 after American researchers saw some success with Asian parasitoid wasps, but the long-term potential of this solution is not yet clear.

In Nova Scotia, another as-of-yet unknown pathogen or other factors are thought to impact black ash trees, causing major but largely unexplained declines since the 1920s. Ash Rust, a fungal disease spread from its alternate host, cordgrass, has been observed occasionally across the Maritimes, but not to an extent that would explain the generalized decline. Ash Yellows is another disease, caused by a phytoplasma bacteria, that attacks the tree’s vascular system and can cause sudden die-back, but this also shows up only infrequently. It’s been suggested that localized and temporary variation in environmental conditions, such as weather, may contribute to die-back. Black ash are shallow-rooted, particularly in shallow, wet, Eastern soils, leaving them vulnerable to freeze-thaw events. Individual trees and groupings of trees seem to respond differently to each of these stressors, with older trees and trees in wetter sites experiencing poorer outcomes, adding to the complexity of the problem.

Black ash in Nova Scotia also seem to suffer from poor seed set, possibly due to this unknown pathogen, combination of stressors, or possibly for other reasons as well. Wisqoq flowers around 30-40 years old, but only produces a large number of seeds every few years. These are known as mast years. The seeds have low viability, averaging 62% germination success across the country but reaching as low as 28% in some parts of Nova Scotia. The seed bank is also very short lived, with seeds remaining viable in the soil for only up to 3 years after dispersal, leaving enough time for the EAB to completely wipe out a forest before trees can re-establish.

Though there’s been limited work done to date to investigate the genetic diversity of Black Ash, as a wind pollinated species it is not thought to exist in genetically-isolated subpopulations. The species is evenly distributed throughout its range, even when spatially rare, and existing research suggests a well-mixed population. One exception to this may be found in Oxford Nova Scotia, where inbreeding is thought to have resulted in lower diversity compared to other areas (Simpson et al. 2008), but this isn’t expected to hamper conservation efforts for the province overall.

In unusual cases, high densities of browsing ungulates like white-tailed deer and moose have contributed to local declines. This was suspected in observed declines on Anticosti Island, Quebec, and in Newfoundland, where ungulates native to neighbouring areas of the Dawnlands have been introduced by humans, but localized browsing is not expected to contribute much to the species’ decline overall.

Ecosystem Effects

Whatever the causes, the large decline expected for Wisqoq will have a significant and lasting effect on the composition and function of the forest it leaves behind. In the Midwest, large ash die-off events have resulted in the conversion of wet forests to open shrublands and meadows, which are more vulnerable to invasion by non-native species like glossy buckthorn and reed canary grass. Few other tree species can tolerate the wet conditions Wisqoq thrives in, making it difficult for native species to re-establish the forest canopy in an ash-dominated forest once it’s gone. Many native arthropods depend exclusively or near-exclusively on ash trees for food or as part of their reproductive cycles, including the waved sphinx, laurel sphinx, and great sphinx moths.

The forests in Nova Scotia have changed dramatically over the last two centuries, with younger and less diverse forest types replacing the previously more common matrix of young and old mixed woods. Wisqoq is sadly just one of many native species that has declined in this time. The biodiversity crisis grabbing headlines in other parts of the world is certainly reflected in the loss of native species here in Nova Scotia.

Take Action

It took action from concerned citizens to get Core Habitat defined for the black ash and it will likely take more action to achieve meaningful conservation for this rare tree. You can help black ash recover by taking both direct action for conservation and indirect action for protecting Wisqoq habitat:

- Follow and support groups like Mi’kmawey Forestry and the Confederacy of Mainland Mi’kmaq at their Wisqoq site, the Nova Scotia Nature Trust, and the Nature Conservancy of Canada, who are working to establish seed collections, reestablish black ash on public and private lands, better understand the issues behind ash decline, and protect lands where Wisqoq grows

- Sign our Ecological Forestry Now petition, demanding the Nova Scotia government finally take meaningful action towards implementing the Lahey Report

- Sign onto our Make Room For Nature letter, asking the province to designate all pending protected areas in the old Parks and Protected Areas Plan and identify the next round of parcels that will move us closer to the new 20% by 2030 goal, prioritizing lands that harbour species at risk like Wisqoq

- Donate to our Wildlife Fund’s Wetland Campaign and help us repeat our World Wetlands Day workshop investigating Gaps in Wetland Protections in Nova Scotia. With enough support we can bring more targeted workshops to communities across Nova Scotia, connecting wetland professionals and members of the public to better understand legislative, policy, and practice gaps leaving wetlands vulnerable to development and destruction.

References

COSEWIC. 2018. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Black Ash Fraxinus nigra in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. xii + 95 pp. (http://www.registrelep-sararegistry.gc.ca/default.asp?lang=en&n=24F7211B-1).

Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources and Renewables. 2021. Addendum to Recovery Plan for the Black ash (Fraxinus nigra) in Nova Scotia – Core Habitat. Nova Scotia Endangered Species Act Recovery Plan Series.

Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources and Renewables. 2019. (Updated) Nova Scotia Wetlands Conservation Policy.

Simpson, J.D., Loo, J.A. and D.A. McPhee. 2008. Genetic Variation of Black Ash in Nova Scotia. Natural Resources Canada Canadian Forest Service – Atlantic Forestry Centre, Fredericton, NB and the Confederacy of Mainland Mi’kmaq, Millbrook, NS. 10 pp.