Don't "drain the swamp!"

A Look Back at World Wetlands Day, February 2nd, 2023

Wetlands provide important ecological, social, and economic functions that are beneficial to Nova Scotians. They minimize erosion and sedimentation of watercourses, provide a buffer against storm runoff and storm surge, store and sequester carbon, sustain biodiversity by serving as important habitats for fauna and flora, support medicinal and ceremonial plants that are important to the Mi’kmaq, and provide hunting and recreation opportunities for the communities that have developed around them.

They’re also disappearing. Around the world, wetlands are vanishing at three times the rate of forests. Urbanization, climate change, and unsustainable development in resource extraction industries have contributed to the loss of 35% of the world’s wetlands between just 1970 and 2015, and the rate of loss has accelerated every year since.

About 1/4 of the world’s remaining wetlands are found in Canada and 10,456sq km are found right here in the Atlantic maritime and highland ecozones. That’s why NatureNS staffers Becky Parker and Jess Lewis were at Captain Spry Community Centre on Feb 2nd, co-hosting two panels on wetland protections with friends at Ecology Action Centre, one for the public and one for wetland professionals. Here’s a bit on what we talked about and what we heard from participants

Wetlands are defined in Nova Scotia by the Environment Act. They are temporarily or permanently wet environments characterized by poorly draining soils, wet-adapted plants, and other biological activities adapted to wet conditions. They are often the intermediate area between environments like lakes, rivers, or streams and drier uplands, though they also include areas that are only temporarily wet, such as vernal pools. Some have rich mineral soils while others are acidic and dominated by peatmoss.

Nova Scotia uses the Canadian Wetland Classification System, which recognizes five general wetland types: marshes (including saltmarshes), bogs, fens, swamps, and vernal pools. Many wetlands exist in a complex of two or more types and may change from one type to another given changing conditions, especially those that change the local hydrology. Generally speaking, though, a marsh contains shallow open water and emergent vegetation like rushes, bulrushes, and cattails. Saltmarshes have saline water because of their position on the ocean, behind barrier beaches, or in estuaries. Bogs, fens, and swamps have acidic and mossy floors with varying degrees of open water and tree cover, and often occur together. Bogs receive most of their water from precipitation alone and contain deep mats of accumulated peat (or Sphagnum) moss and low wet-adapted shrubs. Fens are ground- or surface water-fed and may resemble bogs with streams moving through them. Swamps are similarly peaty and poorly draining but have over 30% tree cover. Vernal pools are small shallow wetlands, often found in forests, that tend to dry out in the summer but provide vital habitat for many breeding amphibians, migratory birds, and other wildlife while they contain water.

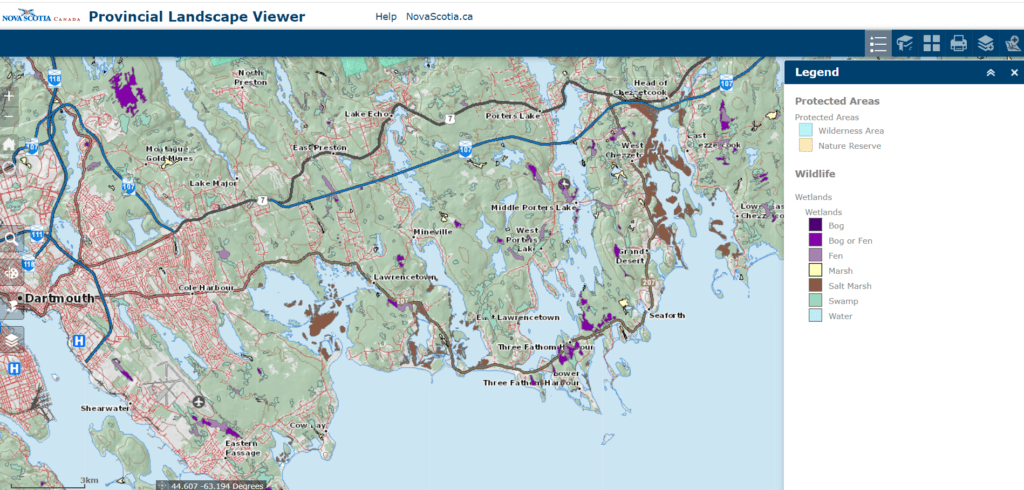

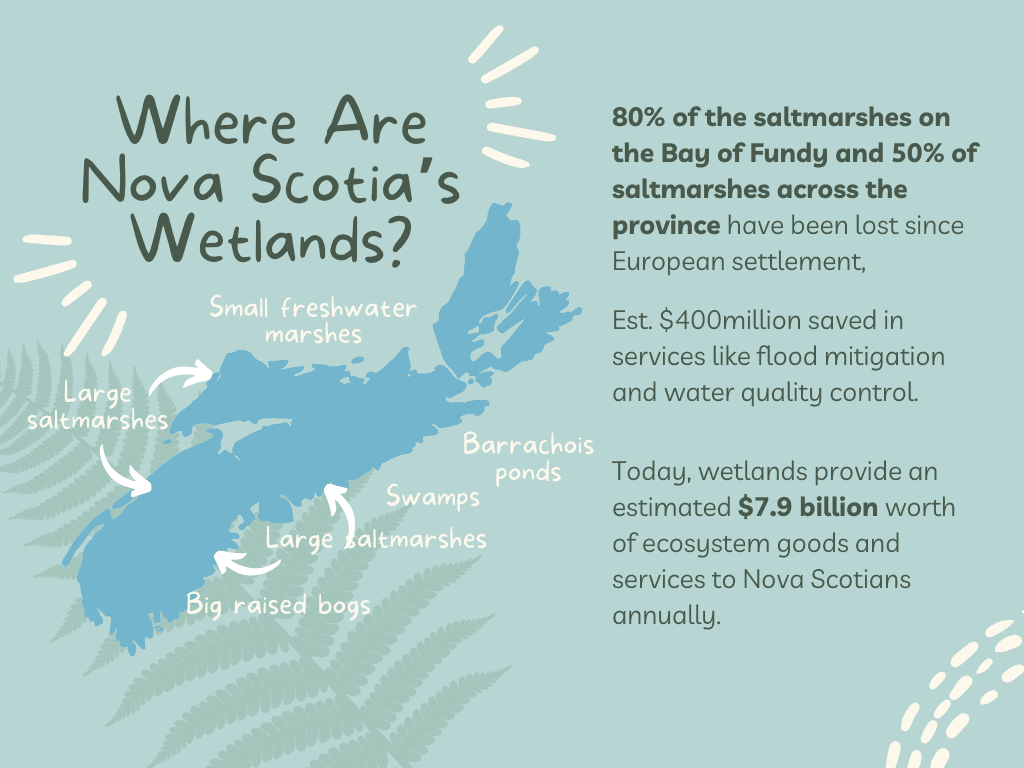

A province-wide inventory of wetlands was completed by the Department of Natural Resources in 2004 and serves as the basis for wetland mapping in the province today. It used aerial photographs from 1985-1997, satellite imagery from 2000-2002, and limited ground-truthing to locate and classify wetlands. Most of Nova Scotia’s wetlands (>75% according to the inventory) are peatlands (bogs and fens), found along the coasts and forming the headwaters of many inland watersheds, followed by swamps, found across the province, and saltmarshes, found in coastal areas with particularly large wetlands along the Fundy and Annapolis coasts and in Southwest Nova Scotia. Freshwater marshes and large floodplain swamps are our rarest wetland types, found adjacent to calm lakes and along the inland portion of large rivers.

An estimated 80% of the saltmarshes on the Bay of Fundy and 50% of saltmarshes across the province have been lost since European settlement, when many were dyked for farmland. Historic freshwater wetland loss is likely higher in the Annapolis Valley, Northumberland Strait, and Shubenacadie River areas, where some of the earliest European farms were created on top of appropriated Mi’kmaq lands. As a result, Nova Scotia has lost many of the significant ecosystem services wetlands previously provided, with the loss of saltmarshes alone estimated at over $400 million in lost services like flood mitigation and water quality control. Today, wetlands provide an estimated $7.9 billion worth of ecosystem goods and services to Nova Scotians, annually.

How Are Wetlands Protected?

Nova Scotia has had a provincial Wetland Conservation Policy since 2011, created in response to a requirement under the Environmental Goals and Sustainable Prosperity Act. It serves as a framework for wetland protection and draws many of its prescriptions from wetland related clauses in several pieces of legislation, including the Environment Act, under an overarching goal of preventing net loss of wetlands. Under this policy, some wetlands are protected from all kinds of development and use through designation as a Wetland of Special Significance. All saltmarshes, for example, are Wetlands of Special Significance, as are wetlands within protected areas and some wetlands known to support Species At Risk or sensitive wildlife habitat. In addition to defining wetlands, the Environment Act also sets out Regulations for alteration approval and environmental assessment, in wetlands not designated as Special Significance. The Wetland Conservation Policy summarizes these prescriptions and creates additional processes for wetland assessment and alteration approval. Wetlands that are not Wetlands of Special Signifiance may be altered by development or other human use if the project can 1) demonstrate few reasonable alternatives to altering the wetland and 2) the wetland alteration can be offset by the restoration or creation of a new wetland somewhere else, at a ratio of at least 2:1 area restored/created wetland to altered wetland.

Wetlands also receive some protection through legislation like the Off Highway Vehicle Act, which regulates ATV use, and the Provincial Subdivision Regulations (under the Municipal Government Act), which

require that the location of any wetland be shown on final subdivision plans. Wetlands with open water receive some protection through the use of a buffer (or Special Management Zone) under the Forests Act, though this only applies to wetlands supporting forestry operations.

Nova Scotia’s Wetland Conservation Policy is a progressive approach to managing wetlands in Canada. Some provinces don’t have any relevant legislation or policies that specifically address wetland loss and, as a result, some municipalities in other areas of the country have been forced to address the need for wetland conservation alone. In many ways, though, wetlands are under-protected in Nova Scotia. Small wetlands are particularly vulnerable to development, which can alter wetlands under 2ha without an Environmental Assessment and wetlands under 100sq m without any kind of alteration approval. Small wetlands are also more likely to be missed in attempts to update the provincial wetland inventory, making efforts at saving swamps and vernal pools, even through Protected Areas planning on public land, very difficult. Though some municipalities may (and have) implement their own best practices, the province does not require buffers for development or other activities adjacent to wetlands, too often resulting in hard surface development right up to the wetland boundary and changes to wetland hydrology. There are no special considerations mandated for forestry operations in treed wetlands like swamps. And, in cases where wetland alterations are approved with compensation, there’s little guiding provincial decision making around what kind of compensation should result from which development. Traditionally, wetland losses to development in urban areas like Halifax (which are largely small peatlands) have been traded for gains in saltmarshes along the Bay of Fundy. Saltmarshes suffering the greatest losses since European settlement, this trade seems reasonable. But taking ecosystem goods and services from one community, one watershed, and/or one traditional Mi’kmaq district, and giving them to another is problematic. So too is the emphasis on physical area as the main indicator of wetland value. Is one small bog worth less than a saltmarsh twice the size? Well, in what way? And to who?

Assessing the Goals of the Wetland Policy

When we get into the details of Nova Scotia’s Wetland Conservation Policy and related legislation, it’s clear there are several gaps leaving some wetlands at risk:

Law vs Policy

Though innovative in some of its approach, the Wetland Conservation Policy is not law, and therefore more vulnerable to sudden change without public consultation than the legislation governing wetlands. Where some protections for wetlands are found only in the policy and not in legislation, this puts the progress made to date and future efforts at minimizing protection gaps at risk of political interference.

Outdated Wetland Inventory

This profile of the province’s wetlands likely needs updating for all wetland types but it may also require improved methodology for detecting small wetlands, which are almost certainly underestimated in the current inventory. Forested swamps were likely underestimated to begin with because of the difficulty in detecting them through remote sensing technologies, but the inventory may also underestimate other wetland types simply due to its age. Without up-to-date and accurate wetland mapping, it is only more difficult for the province, municipalities, and the public to make plans for wetland management and react to development pressures.

Lack of Standards for Development Around Wetlands

The lack of a minimum provincial standard for buffers in development and other activities near wetlands places the burden of understanding and implementing best practices on individual municipalities and landowners. Buffer size and configuration is likely to vary by wetland type, type of development/activity, and expected future pressures on the wetland, and that’s a lot for a small town or individual woodlot owner to navigate on their own.

Lack of Definition for Sustainable Development

The Wetland Conservation Policy, by its own definition, “represents a commitment to managing Nova Scotia’s wetlands in a consistent manner and to maintaining a high level of wetland integrity for future

generations, while allowing for sustainable economic development in our communities.” Though there are standardized methods for both defining a wetland and assessing the potential loss of ecosystem goods and services that wetland provides in the case of a development alteration approval, there is no process for assessing whether a proposed development is “sustainable” or not.

No Place for Mi’kmaq Engagement

Neither the policy or related legislation make requirements for indigenous consultation in wetland alteration assessments. Though under provincial law, wetlands fall into this gray area between public and private ownership, they may always be considered as treaty lands. The Mi’kmaq never ceded lands in Nova Scotia and under still-current Peace and Friendship Treaties, have the right to access resources like wetlands. Many Mi’kmaq people also claim title to these lands. In whichever case the province decides to recognize, the Mi’kmaq should be included in decision making around wetlands, as treaty participants and/or as title holders.

Conflicting Municipal and Provincial Interests

The bulk of the responsibility for managing wetlands falls, technically, with the provincial government, but in reality wetlands are managed across many jurisdictions and wetland conservation goals can conflict with other areas under municipal or provincial jurisdiction, like housing. A municipality may have particularly strong wetland management processes, even going beyond the provincial policy, but lose wetlands to provincial emergency orders or special planning processes. On the other hand, small rural municipalities with few staff and resources may struggle to conserve wetlands on their lands where the province is offering some kind of economic development partnership. Wetlands, whether municipally or provincially owned, may also be sold to private developers just as any dry land can, without public consultation.

Climate Change Complications

Though the Wetland Conservation Policy makes strides in addressing historic wetland loss, it doesn’t do much for setting adaptive goals for the future. Many saltmarshes will need to recede inland in the coming years but existing legislation and policy have few protections for adjacent uplands. The Coastal Protection Act, when it comes into full force, will create a “Coastal Protection Zone” of 80-100m from the sea within which certain regulations will apply (new permits required for development, for example), but it is unclear at this point how these regulations will benefit coastal wetlands, or how anticipated saltmarsh expansion will factor into permitting processes. For other wetland types like bogs and swamps, which offer major contributions to carbon sequestration, it is unclear how the province will factor wetland loss and gains into carbon budgeting and climate change adaptation goals.

No Net Loss?

Without an up-to-date wetland inventory, we don’t know if Nova Scotia is achieving its goal of “no net loss.” The Wetland Conservation Policy does not stipulate that “net loss” should be measured by wetland area alone, though that is the current practice. Unless the province were to commit to an in-depth look at its goals and what it has achieved in the decade since the policy came into being, we really have no idea where we stand on the balance of ecosystem goods and services we may be losing in wetland loss or gaining in wetland restoration/creation. As a result, we cannot say for certain how Nova Scotia is contributing to national or global wetland conservation goals.

What's Next?

We are so grateful for the feedback from participants over our two workshops. Read the full “What We Heard Report” compiled by Dr. Patricia Manuel, Becky Parker from Nature Nova Scotia, Mimi O’Handley from Ecology Action Centre, and staff from Halifax Regional Municipality.

What’s next? We’re working to bring more workshops to communities around Nova Scotia!

We and partners at ACAP Cape Breton, ECELaw, and Mersey Tobeatic Research Institute recently collaborated on an application for funding that would support a year-long deep dive into wetland protection gaps in Nova Scotia, and support 10 community events like this one where wetland professionals and the public can come together to plan a path forward for wetlands. Stay tuned for news on this project!

Other Ways to Get Involved

- Join “Bird Friendly Halifax”, a coalition of nature groups, researchers, and bird loving citizens trying to make our largest city more “bird friendly” through improved city works and local stewardship action.

- Sign our petition for “Ecological Forestry Now” and demand action towards landscape-level working lands planning in Nova Scotia.

- Help us protect the giants of the wetland world, the Mainland Moose, by signing our petition demanding the designation of “Core Habitat.”

- Sign on to our letter asking for an aerial Glyphosate ban and help us protect shared water resources.

Follow our members at Friends of the Pugwash Estuary, Tusket River Environmental Protection Association, Annapolis Waterkeepers, or Friends of Antigonish Harbour for more ways to take action on water issues.