In February, the province released the 6 years-overdue Recovery Plan for the Wood Turtle in Nova Scotia. Here’s an overview of that plan and some information you can use to help Wood Turtles today.

by NatureNS Executive Director, Becky Parker

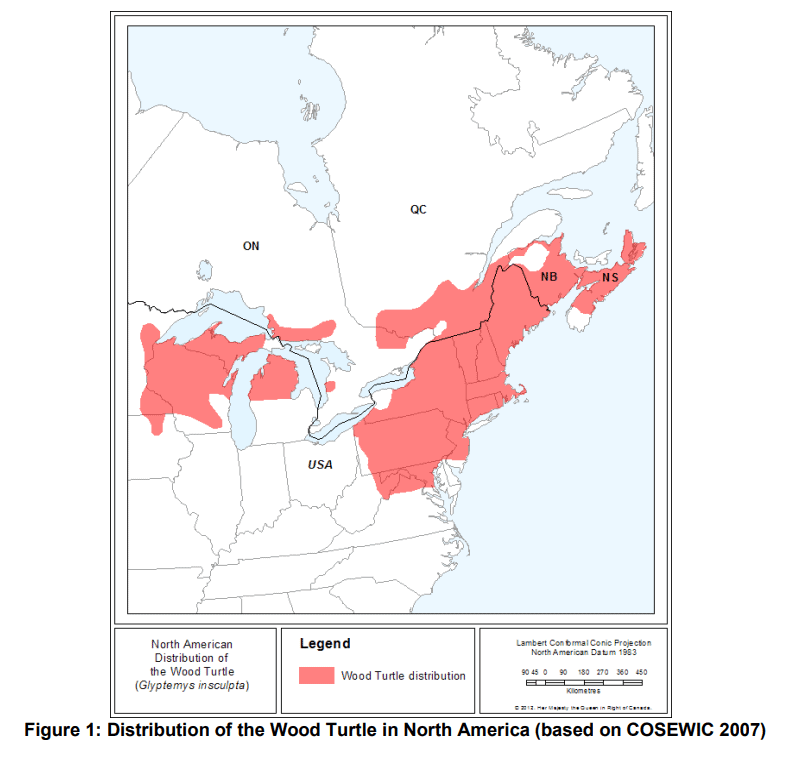

The wood turtle (mikijkj, tortue des bois, Glyptemys insculpta) is a medium-sized freshwater turtle with a grayish-brown shell and an interesting pyramidal growth ring pattern on their scutes. They are found throughout a discontinuous range from Nova Scotia to Minnesota in riparian and other wet habitats, sometimes including wet pastures and farm fields. They nest in sandy or gravelly soils near waterways and may be found in the springtime digging out the sides of roads, driveways, and railways near water.

The wood turtle is in decline throughout its range, due largely to expanding road networks and increased road traffic, shoreline development, modern agricultural machinery, and ATV use on gravel trails. The species was first federally listed as Special Concern in 1996 and reassessed as Threatened in 2007. This status was confirmed in 2018. In Nova Scotia, the turtle was listed under the provincial Endangered Species Act as Vulnerable in 2000 and reassessed as Threatened in 2013.

The wood turtle is also one of the 6 species featured in the Bancroft vs NS Lands and Forestry lawsuit you helped our nature network prepare for last year.

In that judicial review, we alleged that the province failed to establish a Recovery Team and create a Recovery Plan within the legal deadline (which is within two years of listing for Threatened species like the wood turtle, or 2015 in this case.)

In response to this accusation, the legal team for the province asserted that the Minister had adopted the 2016 federal Recovery Plan for the species, which is allowed under the NS Endangered Species Act. However, as our team pointed out, there was no evidence that the province ever actually implemented the federal plan.

When asked for support for their claim that the federal plan had been put in place, such as a public announcement, the formation of departmental committees, delivery of any actions recommended in the report, etc… the province produced a private email from 2014 (two years before the federal plan was finished), from the Director of Wildlife to an official discussing the plan. Notes from the Department made available by request showed that the province had, in fact, considered implementing their own plan draft, dated 2012, in addition to collaborating on the federal plan, but neither of these things ever happened.

“And anyway, we’re working on it…”

The province’s legal team also suggested that our accusations were moot, anyway, because even though a Recovery Plan may or may not exist yet, they did form a Recovery Team. We heard this excuse for other species featured in the review as well.

The Minister did appoint an Amphibians and Reptiles Recovery Team in 2019 (shortly after our judicial review was filed), but this appointment was 4 years late according to the province’s own Endangered Species Act. By the time we went to court in May 2020, the Recovery Plan for the wood turtle was still pending. Judge Brothers agreed that this delay was unacceptable, saying,

We won the case and, in the new year, government formally adopted the 2016 federal Wood Turtle Recovery Plan, under the recommendation of the new Recovery Team.

Ongoing Data and Knowledge Gaps

One of the biggest challenges for the ongoing conservation of the Wood Turtle is a lack of understanding around population trends. Across Canada, the entire population is estimated to be decreasing by 10% every three generations. That’s not a good outlook for a species estimated to include just 6000-12,000 individuals. In Atlantic Canada, there is little data available to inform local actions.

The adopted federal Recovery Plan states that no published population data exists in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. Several surveys have been carried out, however, including ongoing monitoring and stewardship work by Clean Annapolis River Project, the Canadian Wildlife Service, and the Department of Lands and Forestry. Altogether, the Nova Scotian population is expect to range between 2000-7000 individuals, found within 35 primary watersheds.

Under the Precautionary Principle, a lack of data for a listed species should not delay meaningful action. This seems to be the approach taken by the province despite failing to implement an actual Recovery Plan and government’s defense at court.

Provincial grants and partnerships continue to support wood turtle monitoring and stewardship initiatives run by Nova Scotian ENGOs. Existing legislation already requires certain activities maintain setbacks from watercourses and wetlands. Well before adopting the federal Recovery Plan for the wood turtle, the Nova Scotia government did produce a stewardship guide in 2003 that could be used by individuals and stakeholders interacting with turtles. In addition to outlining some best management practices (BMPs) for working around wood turtles, this document also outlined a number of conservation objectives that need to be met “in order to reverse known threats to wood turtles and wood turtle habitat in Nova Scotia”. They included objectives around research and monitoring, sharing information, capacity building, stewardship and education, and habitat management. These are well aligned with the goals outlined in the federal Recovery Plan. Building on this guide, in 2012 the Department also developed a series of Special Management Practices, meant to guide land management decisions in turtle habitat and focused mainly on forestry and agricultural practices. These included clauses like:

- No motorized vehicle use may occur within 100m of either side of a perennial watercourse in known wood turtle areas (as identified by DNR*) in April, May, and October, or within 150m from June to September.

- Use temporary bridge crossings for perennial streams to avoid altering stream bank

- Forest management roads and landings should not be constructed parallel to watercourses within 200m of where wood turtles occur

- Time your work through the seasons of the year to reduce the probability of accidentally harming wood turtles or their habitat

- Leave adequate permanent buffers of vegetation around important wood turtle habitat, a minimum of 30m

- Raise the blades of hay mowers a minimum of 10cm off the ground to help avoid injuring turtles

- Fence all areas used by wood turtles and restrict livestock access in these areas

- Create alternate locations where livestock have access to water, such as by pumping water to designated troughs

*It’s unclear whether “as identified by DNR” (then Lands and Forestry) is referring to core habitat or something else. At the time, core habitat had not been identified…

SMPs should be mandatory for public lands, though at NatureNS we aren’t privy to what kinds of audits and enforcement may take place to enforce these best practices. On private lands, the SMPs are optional but may be incentivized. Many of these landowner best practices could be accomplished by participating in programs like SARPAL (Species at Risk Partnerships on Agricultural Land) administered by Wood Turtle Strides and the Nova Scotia Federation of Agriculture with funding from Environment and Climate Change Canada. They provided landowners with up to $15,000 to help implement BMPs on their farms over 2016-2018. A new SARPAL program in partnership with Clean Annapolis River Project educating landowners on farmland BMPs continues today.

By adopting the federal Recovery Plan, the Nova Scotia government has also adopted the federal definition of “Core Habitat” for the wood turtle. It’s important to note that this federal definition is admittedly incomplete, citing a lack of population data in several watersheds. Provinces choosing to adopt the federal Recovery Strategy and identified Core Habitat may amend the definition. Nova Scotia has not done this. So, currently:

When a minimum of two wood turtle individuals have been observed in any year within the last 40 years, or when a single individual has been observed in multiple years, critical habitat includes aquatic habitat up to the high water mark and 200m inland, as well as 2000m up and downstream from a record and to a maximum of 6000m between two records.

Notice, though, that this definition depends on the confirmed presence of at least one turtle. It’s also important to remember that identifying “Core Habitat” doesn’t automatically offer the turtles any extra protections, as the discretion to implement policies around this area lies with the Minister. Protecting Core Habitat will rely much more on the implementation and enforcement of Special Management Practices, building a culture around stewardship, and incentivizing landowners to adopt best management practices.

How You Can Help Turtles in Nova Scotia

The Wood Turtle is just one of three At Risk turtles in Nova Scotia. You can help all of them by:

- Supporting the organizations that monitor and steward turtle habitats, like Clean Annapolis River Project, the Nova Scotia Nature Trust, and Mersey Tobeatic Research Institute

- Learning more about their biology and ecology, by joining your local natural history society

- Contributing to citizen science initiatives, like the Nova Scotia Herp Atlas on iNaturalist or the province’s SAR reporting system

- Adopting BMPs on your own lands to mitigate damage to nests and habitat. Reach out to groups like Clean Annapolis River Project for help.

- Or reaching out to your MLA to ask them what they are doing to protect turtle populations in Nova Scotia

This is our second update on the SAR featured in the Bancroft vs NS Lands and Forestry case, following a review of the new Recovery Plan for the Rams Head Lady Slipper. We are hopeful that the other species featured in the judicial review will also receive their due protections soon. It is incredibly frustrating when we, as hobby naturalists and retired scientists, must hound our own government to ensure proper adherence to environmental legislation, but we have learned how important it is for citizens to speak up. We will update you when we have more information on the province’s progress towards the rest of Brothers’ orders.

In the meantime, tune into our May “Nature Talk” when we’ll explore the world of natural infrastructure. Read our take on the Biodiversity Act. And make sure you’re following us on social media for more ways you can get involved in our SAR initiatives.

Questions?

Reach out to our staff or board at:

info@naturens.ca

www.naturens.ca