Getting to 30% Protected Areas

Scientists agree that large-scale global protected areas commitments are essential to mitigate the linked biodiversity extinction and climate change crises, helping to conserve species, avoid catastrophic effects of climate change, and secure essential ecosystem services that people and wildlife depend on. In an April 2019 Science article, leading researchers presented a Global Deal for Nature that included land, freshwater, and marine ecosystems and called for protecting at least 30 percent of lands by 2030, with an additional 20 percent of land protected as “climate stabilization areas.”

In 2022, scientists, conservation professionals, and government representatives from all over the world met in Montreal to discuss and ultimately adopt the Kunming-Montréal Global Biodiversity Framework, a historic global framework to safeguard nature and halt and reverse biodiversity loss.

In response to the following United Nations Convention on Biodiversity call for expanded global protected areas, Canada committed to a two-stage expansion of our protected areas system that would bring the country to 30% protected by the 2030 deadline. The federal budget invested $3.2 billion, over five years, to establish new terrestrial and marine protected areas across Canada, including in Nova Scotia. There has never been a bigger investment for nature protection, so it is a milestone worth celebrating!

To help Canada reach this important goal and to deliver on the promises of our own Environmental Goals and Climate Change Reduction Act, the provincial government committed to increasing protected areas to 20% by 2030.

In 2023, the government of Nova Scotia reaffirmed this commitment by signing the $28.5 million Canada-Nova Scotia Nature Agreement with the federal government, unlocking an amazing amount of funding for meaningful conservation efforts in a province that boasts both globally rare and important ecosystems and a multi-billion dollar tourism industry. The agreement specified that Nova Scotia could use the funds to add 82,500 hectares (203,862 acres) to its protected and conserved areas by an interim deadline of March 2026. This would “result in protection for close to 15% of the province’s land mass” and create “a pathway to [achieving] the provincial goal of 20% by 2030, by supporting and accelerating processes that enhance land use planning.” It also required the province to produce regular reports in plain language so that the public could track progress toward the 20% goal and see how funds are being spent.

In the years since, however, the Nova Scotia government has done little to move the needle forward and, given lacking strategy, the abundance of candidate areas still waiting for protection, how many of these areas are pending petroleum or mining rights discussions, and the province’s seeming unwillingness to work with Nova Scotians advocating for the protection of their local wilderness, Nova Scotia is at serious risk of missing the interim 2026 deadline.

Help Us "Make Room For Nature"

Get informed, learn about the pending protected areas near you, and engage your representatives on this important issue. Check out the sections below for more on how our protected areas system works, where gaps are leaving people and wildlife vulnerable, and who exactly we’re fighting to make change:

Protected areas come about in a myriad of ways. Some provincial parks are older than the Provincial Parks Act, having been used as roadside picnic areas for decades before they were actually managed as multipurpose parks. Before wilderness areas were managed as wilderness areas they were just, well, wilderness. Nova Scotia’s protected areas system has evolved from early, sporadic conservation efforts to a comprehensive network of parcels now contributing to wider conservation and recreation goals. In the 1990s, the government of Nova Scotia formally committed to completing a comprehensive system of parks and protected areas which represented landscape diversity and set to work inventorying natural areas and prioritizing areas for conservation. In 2013, it released the Parks and Protected Areas Plan, which identified hundreds of candidate parcels for protection and set out a timeline for their protection. This is still the guiding plan that directs much protected areas work at the provincial level in Nova Scotia.

Today, there are several kinds of protected areas in Nova Scotia, each afforded varying degrees of protection and allowances for different kinds of use or economic activities. This may make public land protection vulnerable to misinformation. In fact, in 2021, following the success of misinformation campaigns targeting the Biodiversity Act, forestry lobbyists concerned about pending protections for the Ingram River area set to work spreading misinformation about the Parks and Protected Areas Plan and the process for protecting Nova Scotia’s wild spaces, going so far as to say that Nova Scotians would lose access to the Ingram if it was formally protected.

Here’s a quick overview of what kinds of protected areas exist in Nova Scotia, how they are managed, by who, and what exactly they are protecting:

-

National Parks: Federally regulated and managed, these protected areas safeguard unique places and ecosystems on federal lands and may provide for light recreation and economic opportunities, such as camping, fishing, or eco-tourism. In Nova Scotia, places like Kejimkujik and the Cape Breton Highlands National Park are managed by Parks Canada and the Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia through The Toqi’maliaptmu’k Arrangement.

-

Marine Protected Areas: Federally regulated and managed, usually by Fisheries and Oceans Canada, these marine areas protect unique or rare marine ecosystems and safeguard habitats for important fisheries species.

-

Provincial Parks: Provincially regulated and managed, these areas protect important natural features on provincial lands and provide recreational, educational, and light economic opportunities similar to National Parks. Provincial Parks are managed by the Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources and receive their legal protection primarily from the Provincial Parks Act.

-

Wilderness Areas: Provincial. These are often the largest, big area and number of, protected areas in Nova Scotia. They are protected for their representative natural features and provide for research, education, some economic activities, and recreation activities such as hiking, fishing, and hunting. They often contain hiking and/or ATV trails stewarded by local or provincial groups. Wilderness Areas are managed by the Nova Scotia Department of Environment and Climate Change and receive their legal protection primarily from the Wilderness Areas Protection Act.

-

Nature Reserves: Provincial. These protected areas are often small, are protected for their unique or rare features and generally limit human use. Nature Reserves are managed by the Nova Scotia Department of Environment and Climate Change and receive their legal protection primarily from the Special Places Protection Act.

-

Municipal Conservation Lands: Owned and/or managed by municipalities, these lands are generally protected through bylaws for the recreation opportunities they provide locals.

-

Private Conservation Lands: These private lands are owned and/or managed by land trusts or private citizens. They are protected by charitable and volunteer action and, depending on the features found within, may receive some protection through legislation like the Beaches Act, Special Places Protection Act, or Trails Act. They may also be open to the public and contain maintained recreation infrastructure like trails. Some kinds of land trusts also pair meaningful conservation efforts with economic activities, like ecotourism or ecological forestry.

Unfortunately, many protected areas in Nova Scotia are not as protected as the public assumes. By 2020, the last deadline for protecting all of the candidate areas in the 2013 Parks and Protected Areas Plan, there were still hundreds of protected areas pending official designation. Many of these areas are still not protected today. Owl’s Head Provincial Park, long assumed to be officially protected, was secretly delisted from the Parks and Protected Areas Plan in 2019 and nearly sold off to a private developer before action from local citizens saved the area. In 2022, the province entertained yet another proposal from the Cabot Group to build a golf course at West Mabou Beach Provincial Park, and citizens again had to come to the rescue. Almost unbelievably, in 2025, the province again entertained the possibility of leasing West Mabou Beach to the Cabot Group, hiding the corporations’ formal application for the park from citizens while the Minister of Natural Resources, Kim Masland, insisted government was “just having conversations” with the developer. The province only announced that it would not further discussions with Cabot under much public pressure.

How many times must citizens fight the same fight for public lands?

The issues aren’t changing – so the legislation has to. Together, we can put pressure on the government to update and strengthen the Provincial Parks Act to ensure that all of our provincial parks and park reserves remain protected forever. Will you sign onto our letter asking government to strengthen protections for these important natural and recreational spaces?

Whether or not and how Nova Scotians should have been consulted before the attempted sale at Owls Head or development deal at West Mabou Beach remains uncertain. Owls Head wasn’t technically a provincial park yet when the province tried to sell it, having been identified as a candidate park waiting for protection in the 2013 Parks and Protected Areas Plan but confusingly listed as a Provincial Park just about anywhere you could find the park’s name. It was only after CBC journalist Michael Gorman obtained a Freedom of Information request that the public learned of the secretive delisting of Owls Head Provincial Park and many Nova Scotians were surprised to learn that the park wasn’t really a park, or was sort of a park…

Our nature network went to court over that very question in 2020, when Nature Nova Scotia President Bob Bancroft and our member organization Eastern Shore Forest Watch argued that government had a duty to consult with the public before agreeing to sell the parcel, even though it was not technically designated yet and only a park in name alone. Justice Christa Brothers decided that such a “public trust doctrine” respecting public lands was not the kind of “incremental change to the common law that [the] court [was] permitted to make”, instead suggesting that if citizens had a problem with any politicians’ decisions they should voice as much at the polls. The Liberal government was shortly after replaced by the current Progressive Conservative government.

It can also be difficult to get new protected areas designated in Nova Scotia. In 2021, the province reached its previous 13% land protection goal with the addition of 80 new sites, including the protection of mature forests of the Sackville River Wilderness Area in Upper Sackville and an expansion for Blue Mountain Birch Cove Lakes Wilderness Area. This helped address a large gap left in the Parks and Protected Areas Plan, which had over 100 sites still waiting for protection at the time. These gains were hard-won though.

Take the Ingram River for example…

The Ingram River area is a matrix of public and private lands supporting some of the most pristine wilderness left on St. Margarets Bay, including old forests, habitat for many provincially and federally listed species at risk, and some of the best hiking, hunting, and fishing opportunities in the Halifax area. Locals have been trying to get it protected for years. Additions to the existing protected parcels along the Ingram River were released for consultation in Fall 2021 and immediately faced a misinformation campaign by WestFor Management Inc, which happened to operate a crown logging lease in the area. WestFor suggested through their Facebook presence and a news interview that, under protection, the Nova Scotian public would no longer be able to access the area, despite government openness to ATV and snowmobile use and the fact that all Nova Scotians have the legislated right to access forested lands for many purposes. This narrative comes up again and again when big forestry interests are threatened by conservation initiatives.

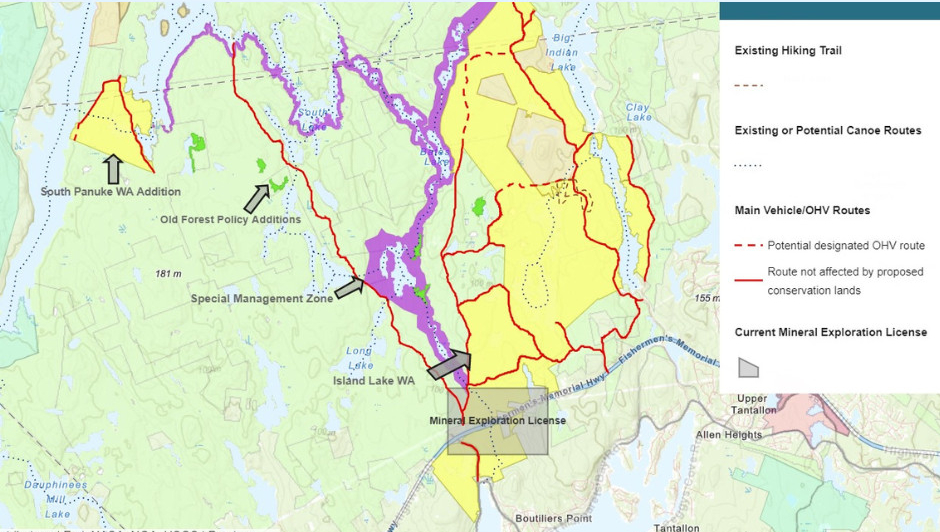

The proposal for the Ingram River included the addition of lands to the existing South Panuke Wilderness Area, designation of the new Island Lake Wilderness Area, creation of a special management zone along the Ingram River waterway, and protection of additional lands under the Old Forest Policy. The South Panuke Wilderness Area addition was part of a volume-based crown forestry license. Now protected, government amended its license with the company to remove these lands (and only these lands) from the license. The northern side of the proposed wilderness area addition bordered on a large block of public land that is part of the Mi’kmaw Forestry Initiative (MFI). This is a forestry pilot project that gives the Mi’kmaq forest planning and management responsibility on designated public parcels, through the guiding principles of Netukulimk, and it is unaffected by the new protected areas designations. The 888ha Special Management Zone (SMZ) proposed for the valley corridor would not allow for forestry activities. This area forms a thin buffer around watercourses, wetlands, and other sensitive habitats that are inappropriate for forestry operations anyway. The areas added under the Old Forest Policy included 54ha of old-growth and near old-growth forest. This hectarage was so small compared to the rest of the proposed conservation lands that it could not reasonably be considered to negatively impact forestry interests. It will, however, significantly benefit the conservation of declining old forest species in the area.

As for recreational access, all Nova Scotians have the legislated right to cross forested land for the purpose of fishing and hunting, especially public land, including Ingram River. Wilderness Area also allow for hunting, fishing, and even ATV use in designated areas. In fact, the Department of Environment and Climate Change had already indicated that it would amend existing provincial trail management agreements with the All Terrain Vehicle Association of Nova Scotia (ATVANS) and Snowmobilers Association of Nova Scotia (SANS) to allow continued ATV and snowmobile use on essential connecting routes through the proposed Island Lake Wilderness Area, which is the larger of the two in this example.

All together, the protection of the Ingram River was a very small step towards better conservation of an area that supports 18 confirmed species at risk and provides countless dollars in ecosystem goods and services every year, including through Mi’kmaw-led industry. The only Nova Scotians who didn’t benefit from the new Ingram River designations were those who wanted to clearcut it.

Where Do We Stand Today?

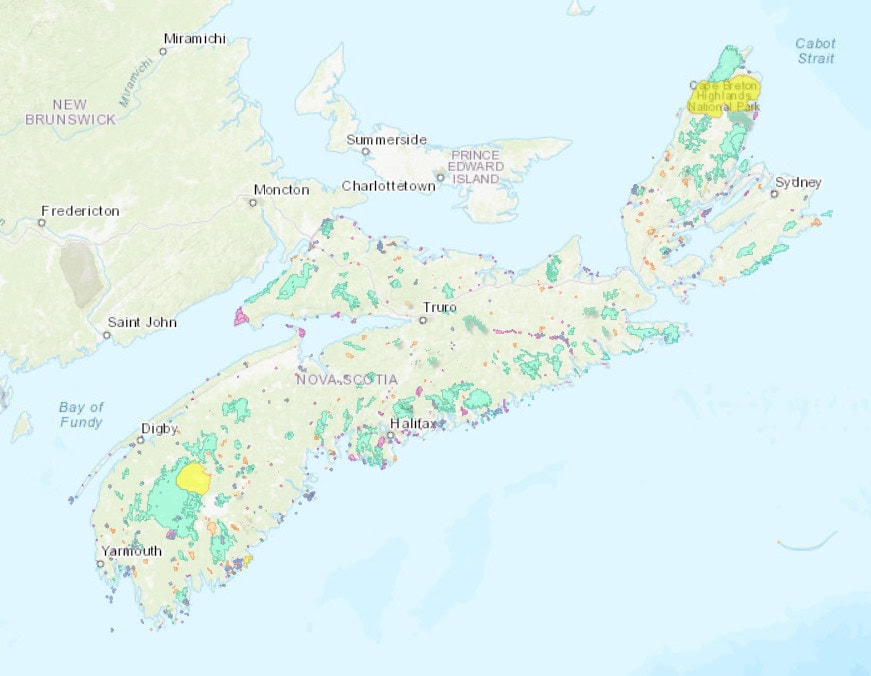

After slow but steady progress protecting public lands identified in the 2013 Parks and Protected Areas Plan, the province suspiciously stopped designating new protected areas for several months in 2024, leaving many of these pending parcels unprotected. The Nova Scotia government also has not produced any of the reports required as part of the federal funding agreement. As of winter 2026, Nova Scotia is sitting at just under 14% protected lands, less than 4 years away from the 2030 deadline for protecting 20%.

As we wait for the province to pick up the slack or, at minimum, provide a reason for the lack of action, we are increasingly concerned that the delay may be intentional. Most of the 2013 Parks and Protected Areas Plan parcels that are still unprotected are listed in the Plan as “delayed to 2020” due to “addressing mineral” and “petroleum rights,” or “wood supply.” We think the province is intentionally delaying formal protection for these public lands so that industry can take what they want, first.

Citizens Step Up To Fill The Gaps

While the province drags its feet, Nova Scotians are stepping up to protect local wildernesses through citizen science, petition signing, and direct action. Nova Scotia doesn’t have a formal process for protecting citizen-nominated protected areas. The public land parcels identified as candidates for protection in the now outdated Parks and Protected Areas Plan were the result of a lot of internal scientific work, some collaboration with external environmental experts and industry representatives, and little meaningful public consultation.

When the province released the new Collaborative Protected Areas Strategy in 2023, intended to act as a guide towards achieving the 20% by 2030 goal, there was no commitment to include citizens in the planning stage of the province’s existing land protection process. Considering that the province also didn’t identify any of its own new candidate protected areas through this “strategy”, many in the natural history community were left wondering what the document even existed for. This is a serious gap, as local citizens often have useful information about public lands that can benefit land use planning and management, but also because public buy-in is essential for maintaining the environmental and cultural values protected areas are protected for in the first place.

Check out a few of the places locals are trying to protect – through citizen science work documenting old forests and species at risk occurrences, through petition signing, and direct action:

Much of Sandy Lake is still awaiting legal protection. In 2022, the province identified Sandy Lake as an area they would fast-track desperately needed housing development, despite existing plans and municipal support to finish the Regional Park and outcry from scientists, hobby naturalists, and the public. Write to the Premier, your MLA, and municipal councilor and ask them to finally protect this rare wild gem in the city.

The Blomidon Naturalists Society is proposing a new wilderness area for public land in southwest Kings County. The southwest corner of Kings County is the only major section of public land in the County that remains largely forested without human habitation. To date, there has been little opportunity or process for citizens to suggest public lands for formal protection. Take action today and help BNS protect this last wilderness.

The forests surrounding Goldsmith Lake are old, diverse, and support 95 confirmed species at risk. The Citizen Scientists of Southwest Nova Scotia submitted a proposal to the Dept. of Environment and Climate Change to protect an area of 3900 ha of Crown land surrounding Goldsmith Lake in 2022. Help the Citizen Scientists and Save Our Old Forests get this forest protected by signing onto their petition.

The proposed Ingram River Wilderness Area is a treasured community wilderness on the outskirts of Halifax, containing beautiful canoe routes, the oldest hemlock tree on record, and several resident species at risk. Locals want to give this area second chance – a chance to recover, where forests can grow old again and wildlife can return. Help the St Margarets Bay Stewardship Association and allies protect Ingram River from corporate capture and government inaction.

Take Action

Sign onto our letter asking government to designate all remaining pending protected areas in the now out-of-date Parks and Protected Areas Plan and get to work on a robust new plan for achieving 20% by 2030. Copy the text below, edit as you see fit, and send then send it in an email or print mail to the Premier, Minister Halman, and your MLA:

“[Minister Halman, Premier Houston, and/or your MLA],

Following the federal government’s example and call from the IUCN to increase the amount of land and oceans under formal protection, in 2021, the province renewed its commitment to nature with a promise to protect a total of 20% of Nova Scotia’s public lands by 2030. This a 7% increase from the previous 13% goal, which I was happy to see the province achieve in 2021. Shortly after, government launched a new planning process for identifying the next round of protected area parcels. I am concerned that this process only included the short 6-question survey government sent out, and not meaningful consultation with scientists, conservation groups, hobby naturalists, or other members of the public. I am also concerned with how many parcels identified in the now outdated Parks and Protected Areas Plan are left undesignated, as we approach the end of the 2030 timeline.

The Parks and Protected Areas Plan built on previous planning documents and identified additional areas that would require more planning, restoration, or other work before protection but that could have brought total land protection in Nova Scotia to 15%, had they all been designated by the 2020 deadline. I understand that some delays in designating candidate protected areas must be explained by logistical issues, such as acquisition, research, or other needs. But looking at these still pending parcels and the reasons for delayed designation given in the Plan, the vast majority seem to be awaiting clarification on mineral or petroleum rights. So it would seem that this government is intentionally avoiding protecting public lands in order to allow for unsustainable natural resource development. This is unacceptable. It’s time our province designated all remaining pending protected areas in the old Parks and Protected Areas Plan and started work on a new (and full) plan that will take us into the next decade.

Your latest Protected Areas Strategy survey asked Nova Scotians very broad questions like “what are some barriers to achieving 20% protected areas?”, “how can private landowners be encouraged to contribute to the 20% goal?”, and “what should government consider in identifying new protected areas?” but you don’t ask us the more meaningful questions of “where would you like to see protected areas created or expanded?”, “which organizations, industry groups, and citizen groups would you like to see engaged in this next round of protected areas planning?”, or “how can government create more opportunities for public engagement as this process continues?” Surely those 6 simple questions you’ve put to Nova Scotians through this survey do not constitute the entirety of the public consultation your new Protected Areas Strategy will be based on…

Citizens are mobilizing to protect areas like Ingram River, Goldsmith Lake, and Chain Lakes, often racing against harvest activity as they gather old tree and species at risk sighting reports to give your Natural Resources and Environment Department’s staff. Please designate all remaining provincial parks, nature reserves, and wilderness areas across Nova Scotia and provide citizens with an update on your full process for the next round of protected areas planning, including how we might formally nominate areas for protection, how we might contribute citizen science data, and how we might provide feedback on the draft plan once it’s ready.

Sincerely, [Your Name]

[Community], Nova Scotia

Can You Go A Step Further?

1) Explore the Protected Areas Viewer to learn about existing and pending protected areas near you, then reach out to your MLA and ask them what they’re doing to ensure we meet our protected areas commitments.

2) Prepare for a disappointing response and be ready to follow up. Did you get a generic response reiterating the province’s supposed commitment to nature protection and detailing what they have done? Focus your response on clarifying questions like “Why have no protected areas been designated in the last year?” “Who, specifically, are you engaging in your work to move [your local pending protected area] towards official protection?”, and “Do you mean to say that government has no intention to release a full 20% Protected Areas Plan, incorporating citizen knowledge and desires for community-nominated protected areas?”

3) Contact your MP and tell them you support the 30% by 2030 national protected areas goal.