Nature In Nova Scotia Is Under Threat

Where do we start? Though required to protect 20% of lands and waters by 2030, the province is so far behind schedule that only a handful of new protected areas have been designated since Premier Houston’s first term. Meanwhile, lands that are still under assessment for protection are being clearcut as companies scramble to take what they can, while they can. To make matters worse, last winter, the province tabled several bills aimed at opening previously banned natural resource extraction activities, reducing public access to information about government decision making, and attempting to reduce the powers of the Auditor General. All without public consultation or link to government’s current mandate.

We are concerned that government is getting ready to sell the province to wealthy foreign industry empires by making it harder for Nova Scotians to participate in the democratic processes that inform natural resource management decision making.

Join Us As We Mount A Defence

We are mobilizing Nova Scotians into actions to protect our shared natural capital. Start by understanding the issues at hand then join us at an event or take action on your own.

Understand the Issues

Backgrounders By Topic:

Fracking is the process of injecting a high-pressure mixture of water, sand, and thickening agents into the ground to fracture rock formations, giving access to natural gas deposits. In 2014, the provincial government imposed a moratorium on fracking following review of other jurisdictions and extensive consultations with the public and Mi’kmaw communities. Fracking presents risks to water quality, public health, and to existing industries including natural resource based businesses.

Nova Scotia is (supposedly) committed to a transition away from fossil fuels and towards green energy operations that will reduce energy costs for the average Nova Scotian and help us meet carbon emission goals. Natural gas burns more cleanly and emits less carbon dioxide than coal, but the risk of methane leakage associated with fracking may cancel out the greenhouse gas budgeting benefit of transitioning from coal to gas. This is one of many reasons why experts are pushing for more reliance and investment in wind and solar.

Fracking for natural gas is banned either temporarily or permanently in Quebec, New Brunswick, and Newfoundland, as well as many American states and across entire nations. In Newfoundland and Nova Scotia, the particularly strong opposition to fracking that eventually resulted in the original bans came from small rural communities who organized to protect their local areas.

Reversing the ban on fracking in Nova Scotia will undo the decades of consultation that has already occurred and threatens Nova Scotia’s contribution to global climate change mitigation goals.

Quick Fracking Myth Busting:

Fracking is safer than it was in the past.

Answer: Fracking still uses large volumes of surface water and still results in chemical and methane leaks that can impact drinking water resources. Nova Scotia does not have baseline information about the quality and quantity of groundwater in the rural communities where fracking would occur, making risk assessment difficult. Moreover, even with improvements, fracking for fossil fuels still makes it that much more difficult for Nova Scotia to achieve climate change mitigation goals.

Fracking in Nova Scotia will be temporary and create jobs that benefit rural communities.

Answer: Watching other jurisdictions deal with fracking, it’s clear that fracking operations create only a handful of temporary jobs while also being incredibly expensive to operate.

Gas is cheaper home heating for the average Nova Scotian.

Answer: Electric heat pumps are almost always more cost effective for home heating because of their high efficiency. While having multiple power sources is important for the security of the home grid, efficiency and environmental sustainability often go hand in hand. Beware of attempts at greenwashing fossil fuels.

If you drive a car, you can’t advocate for a fracking ban.

Answer: Did you know fossil fuel companies were the first voices to popularize the idea of a “personal carbon footprint?” Even in wealthy nations like Canada, personal carbon footprints are miniscule compared with industrial. Collectively, the use of personal fossil fuel-powered vehicles is an important contributor to climate change. However, individual Nova Scotians are not responsible for the car-dependent transportation network our decision makers have set up through poor planning and capture by corporate interests over the decades. While we advocate for greener energy sources to power our industries as well as our daily lives, it is also important that we advocate for smarter community and transportation planning. Comments like this suggest that we are stuck in a car-dominated culture forever when, in reality, we could choose do better.

More on fracking in Atlantic Canada and how we can protect our communities:

- “Keeping the “Know” in Nova Scotia: The facts about fracking & the renewable energy transition in Nova Scotia” Ecology Action Centre, March 2025

- “The EAC’s Statement on the NS government’s decision to alter legislation on fracking and uranium mining”, Ecology Action Centre, Feb 19, 2025

- “A brief history of fracking in New Brunswick in the context of the provincial election”, Angela Giles, the Council of Canadians, October 4, 2024

- “New Brunswick physicians call for permanent ban on fracking due to unacceptable health risks”, Canadian Association of Physicians for the Environment, May 9, 2024

- “Sample resolution: Pass a municipal resolution in your community against fracking”, Council of Canadians, Feb 26, 2020

- “Toward an Anti-Fracking Mobilization Toolkit: Ten practices from Western Newfoundland’s Campaign” Angela Carter and Leah Fusco, Dec 2017

- Report of the Nova Scotia Independent Review Panel on Hydraulic Fracturing, Atherton et. al., August 2014

- “Keep it in the ground: The impacts of fracking in Nova Scotia”, Ecology Action Centre, April 2014

- A Fracktivists Toolkit, Council of Canadians, Feb 2014

Lithium is important mineral in the global movement towards cleaner technologies, especially in electric vehicles and renewable energy storage. Demand for lithium has surged in recent years and both the Government of Canada and the Province recognize lithium as a “critical mineral,” promoting mining as part of the green energy transition. However, the concentrations of Nova Scotian lithium deposits are low and mining these small stores comes with a high environmental cost.

Like many other kinds of mining, lithium mining requires large amounts of water and energy and leaves behind polluted environments that need to be remediated. Nova Scotia’s lithium deposits are largely located in the Annapolis Valley, an important agricultural hotspot and home to a large proportion of our population.

The province generates revenue from mining through royalties paid by companies. As a result, mining does not contribute substantially to Nova Scotia’s GDP. Given how little and inaccessible Nova Scotia’s lithium stores are, it is not likely to be a productive industry, at least certainly not when compared with existing agricultural and natural resource-based industries.

More on lithium mining and other supports from our friends:

- “Keeping the “Know” in Nova Scotia: The facts about lithium mining & battery recycling in Nova Scotia”, Ecology Action Centre, March 2025

- “Summary: Lithium Mining in Mexico – Public interest or transnational extractivism?” Mining Watch Canada, Feb 23, 2023

- “Impacts of Mining Activities on Water: A technical and legislative guide to support collective action”, Mining Watch Canada, Nov 21, 2023

- “Canada’s Critical Minerals Strategy – A Response to the Department of Natural Resources Discussion Paper”, Mining Watch Canada, Sept 15, 2022

Before Nova Scotia legislated a ban on uranium mining, we had a moratorium on exploration instituted by a Conservative government. Previous exploration for uranium on public and private land angered Nova Scotians, especially in rural parts of the province, and a grassroots movement emerged to push for the ban. Several municipalities supported the provincial ban for concerns over the health of their communities and natural environment.

Though uranium is listed as a critical mineral for its potential role in helping Canada transitioning away from carbon based energy sources, we are far from experiencing a shortage of it, nor do experts agree that Canada needs more nuclear energy generators. One of the planet’s largest uranium deposits is located in Northern Saskatchewan and it is already being mined, with the majority of production exported to the States. The current stock market crisis around uranium, which is strategically cited by government and mining lobbyists in Nova Scotia as a reason to mine for uranium here, has less to do with real uranium supply and more to do with self-inflicted political instability in the United States, which is affecting that nation’s ability to secure uranium from the world’s biggest producers, Canada and Kazakhstan. The Nova Scotia government’s attempt to develop a uranium industry in a province that cannot possibly compete with other jurisdictions and that does not have a nuclear power plant (and likely will not, as these facilities can take decades to build) is therefore needlessly reckless.

Other jurisdictions are moving away from nuclear as they transition to green energy options. Uranium mining uses a large amount of water, which is then contaminated and must be remediated. Tailings are radioactive for thousands of years after mining and must be stored carefully to avoid leaking radiation to the environment and communities. Uranium is typically mined in an open-pit operation similar to how gold is mined in Nova Scotia, having an extensive impact on the landscape it is situated in.

Given Nova Scotia’s experience with another unnecessary resource, gold, Nova Scotians are right to be nervous about opening the province up to uranium mining. During the 6 years the Touquoy open pit gold mine operated, the company broke 23 provincial and 3 federal laws that were in place to protect the environment and is now in a lawsuit with the Nova Scotia Department of Environment and Climate Change attempting to avoid their required their mine remediation.

Quick Uranium Myth Busting:

Why is uranium dangerous? Isn’t there uranium in our smoke detectors, as mining lobbyists in Nova Scotia have claimed?

Answer: Smoke detectors use americium, a synthetic isotope made (in cyclotrons) from plutonium, not from uranium. Uranium mining has become much safer in recent decades, but there are still significant human health and environmental risks to consider, especially in a province so densely populated.

Do credible geologists need to be certified by the Association of Professional Geoscientists of Nova Scotia?

Answer: No. This certification, like other provincial certifications, evolved partly out of the Bre-X Minerals Ltd scandal in the 90s. Bre-X was a Canadian mineral exploration company that announced the find of a massive gold deposit in Indonesia in 1995, leading to a rush of share buying, but which turned out to be false. Canadian jurisdictions adopted the ‘licensed geologist’ designation shortly after, which is meant to assure the public that the licensed professional has the qualifications to make statements on risky topics. It also protects geoscientists against getting sued. Many geoscientists don’t need to be licensed because they don’t make risk-based statements meant to stand up in court. Academics, for example, who don’t do resource evaluations or natural risk assessments are still knowledgeable regarding these issues and may comment on geology topics that affect the public or our shared natural environment.

More on uranium mining and other supports from our friends:

- “Keeping the “Know” in Nova Scotia: The facts about uranium exploration & mining in Nova Scotia”, Ecology Action Centre, March 2025

- The Trouble With Uranium in Nova Scotia, Dr. Elisabeth Kosters in the Halifax Examiner, June 2025

- Debunking Nova Scotian Politicians and the Mining Association of Nova Scotia’s Claims About Uranium, Geologist Dr. Elisabeth Kosters, July 2025

- Geoscientists Nova Scotia threatens people opposed to uranium mining with fines, jail time, Joan Baxter for the Halifax Examiner, July 2025

- “Impacts of Mining Activities on Water: A technical and legislative guide to support collective action”, Mining Watch Canada, Nov 21, 2023

- “Canada’s Critical Minerals Strategy – A Response to the Department of Natural Resources Discussion Paper”, Mining Watch Canada, Sept 15, 2022

The Wabanaki-Acadian forest is a mixed temperate woodland characterized by diverse hardwood and softwood species and a wind-dominated disturbance regime. In Nova Scotia, as elsewhere in the Maritimes, the rise and continuance of industrial forestry in the 19th and 20th centuries has left a legacy of disappearing old forest, more even-aged stands, and a patchwork of mostly young forests interrupted by clearcuts.

Recognizing a reliance on outdated assumptions about the Wabanaki-Acadian forest, how it might respond to intensive harvest pressure, and the need to transition to landscape-based ecological forestry practices, Nova Scotia commissioned and subsequently adopted the recommendations of Prof. William Lahey’s 2018 Independent Review of Forest Practices in Nova Scotia, which premised that diverse, older, and natural forests are the foundation for all the economic, ecological, and social benefits that Nova Scotians get from the Wabanaki-Acadian ecozone.

The Lahey Review called for a triad model for public lands management that split forests into three categories: production forests, protected forests, and the ecological matrix, which would allow for ecological or “light-touch” forestry. Though the review was widely accepted by eNGOs like ours and province has formally adopted the review as an overarching guide for how forestry is to be implemented and regulated in Nova Scotia, little progress has been made in actually delivering on the document’s goals.

Forests that support species at risk, exemplary old trees, and other conservation values are being clearcut, even as locals organize in an attempt to have these areas formally protected. At Ingram River, Goldsmith Lake, Beals Brook, and other areas, locals are organizing to save some of the last wilderness left in Nova Scotia.

Learn more about the overdue transition to ecological forestry via:

- The Healthy Forest Coalition’s blog, a collective of foresters, researchers, NGOs representatives, and others pushing for a more sustainable future for forestry in Nova Scotia

- William Lahey, “An Independent Review of Forest Practices in Nova Scotia: Executive Summary Conclusions and Recommendations” (Halifax: Government of Nova Scotia, 2018).

- William Lahey, “An Independent Evaluation of Implementation of the Forest Practices Report for Nova Scotia” (Halifax, 2021)

Wetlands provide important ecological, social, and economic functions that are beneficial to Nova Scotians. They minimize erosion and sedimentation of watercourses, provide a buffer against storm runoff and storm surge, store and sequester carbon, sustain biodiversity by serving as important habitats for fauna and flora, support medicinal and ceremonial plants that are important to the Mi’kmaq, and provide hunting and recreation opportunities for the communities that have developed around them.

They’re also disappearing. Around the world, wetlands are vanishing at three times the rate of forests. Urbanization, climate change, and unsustainable development in resource extraction industries have contributed to the loss of 35% of the world’s wetlands between just 1970 and 2015, and the rate of loss has accelerated every year since.

An estimated 80% of the saltmarshes on the Bay of Fundy and 50% of saltmarshes across the province have been lost since European settlement, when many were dyked for farmland. Historic freshwater wetland loss is likely higher in the Annapolis Valley, Northumberland Strait, and Shubenacadie River areas, where some of the earliest European farms were created on top of appropriated Mi’kmaq lands. As a result, Nova Scotia has lost many of the significant ecosystem services wetlands previously provided, with the loss of saltmarshes alone estimated at over $400 million in lost services like flood mitigation and water quality control. Today, wetlands provide an estimated $7.9 billion worth of ecosystem goods and services to Nova Scotians, annually.

Nova Scotia has had a provincial Wetland Conservation Policy since 2011, created in response to a requirement under the Environmental Goals and Sustainable Prosperity Act. It serves as a framework for wetland protection and draws many of its prescriptions from wetland related clauses in several pieces of legislation, including the Environment Act, under an overarching goal of preventing net loss of wetlands. Under this policy, some wetlands are protected from all kinds of development and use through designation as a Wetland of Special Significance.

In many ways, though, wetlands are under-protected in Nova Scotia. Small wetlands are particularly vulnerable to development, which can alter wetlands under 2ha without an Environmental Assessment and wetlands under 100sq m without any kind of alteration approval. Small wetlands are also more likely to be missed in attempts to update the provincial wetland inventory, making efforts at saving swamps and vernal pools, even through Protected Areas planning on public land, very difficult. Though some municipalities may (and have) implement their own best practices, the province does not require buffers for development or other activities adjacent to wetlands, too often resulting in hard surface development right up to the wetland boundary and changes to wetland hydrology. There are no special considerations mandated for forestry operations in treed wetlands like swamps. And, in cases where wetland alterations are approved with compensation, there’s little guiding provincial decision making around what kind of compensation should result from which development.

In September 2023, the Nova Scotia Department of Environment and Climate Change quietly circulated an internal memo detailing changes to how the Nova Scotia Wetland Conservation Policy (the “Policy”) would be interpreted, specifically concerning Wetlands of Special Significance (WSS), to its staff. The changes reduced the power of the Policy to protect WSSs that the province arbitrarily deemed important for development and were effective immediately. The memo was leaked and environmental groups, including Nature Nova Scotia, denounced the changes in a statement released by Ecology Action Centre. In August 2025, the province rejected Halifax Regional Municipality’s new regional plan for, among other reasons, including a modestly increased wetland buffer for new developments, saying that it would impede housing development… but with no regard for the essential flood mitigation value of urban wetlands.

Learn more about current gaps in wetland conservation in our What We Heard Report from World Wetlands Day 2023.

Attack on Nature & Democracy, A Timeline:

What Can We Learn From Other Jurisdictions?

- Elsipogtog First Nation in New Brunswick and settler allies successfully pressured Texas-based fracking company SWN to stop fracking on Mi’kmaq land following conflicts that prompted protest organizing and road blockades in 2013. The people raised concerns about government’s failure to consult with them before allowing for fracking and, not being heard, organized action to defend treaty lands and pushed SWN out by that winter. Not only that, but the conflict is credited with being a driver behind the election of a new government shortly after. New Brunswick would eventually introduce a moratorium on fracking in 2016.

- Protests and civil disobedience prevented multiple gas companies from opening new fracking wells in the Saint Lawrence Valley in Quebec over 2010-2013. The movement brought together farmers, hunters, first nations, and others who would eventually block the Energy East crude oil pipeline and get Quebec to commit to banning future development, forever, making the province the first jurisdiction in the world to ban oil and gas extraction. The efforts of Ristigouche Sud-Est township were particularly impressive. Just 157 people came together and passed a bylaw in 2013 that set out a 2km no-drill zone around its water supply. Gastem, the oil and gas company, served the town a lawsuit claiming residents had created an illegal bylaw to prevent the project from moving forward, but lost when the superior court of Quebec ruled that the town was within its rights to protect their water supply.

- France banned fracking in 2011 hearing significant public concern around environmental and climate impacts. France later adopted law banning new fossil fuel exploitation projects and committed to closing current ones by 2040.

- Most of Germany’s natural gas came from domestic fracking operations until public pressure, criticism from many NGOs, and support of opposition parties resulted in a moratorium and then law banning fracking in 2016. The energy crisis set off by Russia’s occupation of Ukraine has reignited discussion about fracking in Germany, but so far, the government and public seem to agree that fracking offers little benefit to the country while introducing significant risk.

- Farmers and environmentalists organized in Ireland to get fracking banned onshore and within internal waters in 2017. Promises of development resulting in local jobs brought and the unavoidable conflict with farming and fishing lifestyles brough neighbours into conflict with each other. Direct action was violently suppressed and the mainstream media largely sided with developers, furthering local tensions. So organizers were careful to build community, organize in a decentralized and local way, and to centre campaigns around public health.

- Growing concerns about pollution and the occurrence of two small earthquakes in the mid 2000s culminated in the creation of fracking opposition group Frack Off and other protest movements in the United Kingdom. Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland have temporary or permanent moratoriums and, though government recently lifted a moratorium, in 2022, England sealed and abandoned its only two shale gas wells.

Take Action

Come To An Event

Find your MLA. Arrange for an in-person meeting if you can. Make it clear that you live in the riding, which dates and times you are requesting, and exactly what you wish to discuss. Be calm, be kind, but be clear and make sure they hear you. Be prepared for some politicians to try to take over the meeting or mislead you with inaccurate information, and be concise, as you will likely have only 30 minutes at most. Check out this helpful how-to engage your elected official resource from Ecology Action Centre.

Your local council could be allies in the fight to protect human and environmental health. Talk to your councilor and ask for their help introducing a resolution or other local law to prevent fracking, lithium, or uranium exploration, or ban the industries altogether. Find examples from the Council of Canadians (fracking specific but a good starting place for lithium or uranium.)

Annapolis, West Hants, Lunenburg, and Pictou Counties have all asked the province to pause before issuing any new uranium exploration licenses. Each counties’ motions varied, but each agreed to formally ask the province for an indefinite delay so that their communities can become better informed about potential impacts. This is a great start!

Formal designation as a national, provincial, or other kind of protected area offers varying safeguards to public lands at risk of fracking, lithium, uranium mining, and clearcutting. It’s not foolproof, but it helps, and this is exactly why mining and forestry industry empires hate the protected areas system. Nova Scotia is committed to protecting 20% of public lands by 2030. Put pressure on government to deliver on this promise by contacting your MLA, signing a petition, or taking other actions.

The Assembly of Nova Scotia Mi’kmaw Chiefs has criticized Premier Houston for not consulting with the Mi’kmaq in advance of revealing government’s new push for previously banned natural resource extraction industries. The Nova Scotia government, as a representative of the British crown, not only has a Constitutional duty to consult the Mi’kmaq on any activities that may impact Treaty rights, but according to the Peace and Friendship Treaties themselves must recognize Mi’kmaq title to all lands and waters in Nova Scotia. Though government has often neglected its Treaty obligations, by law no decision can be made that could reasonably affect Mi’kmaq Treaty rights without first consulting with the Mi’kmaq.

Remind government of this fact by contacting your MLA and participating in Mi’kmaq-led action when invited. Can you go a step further? Contact the British crown’s representative in Nova Scotia, Lieutenant Governor Mike Savage, and express your personal commitment to our shared Treaty obligations.

Direct action is a broad term describing many kinds of immediate action-taking, most of which are usually legal, such as protest, strike action, and boycotts. Civil disobedience is a historic change-making tactic that employs direct and non-violent means of violating law. International human rights standards recognize civil disobedience, when non-violent, as an expression of rights to freedom of conscience, expression, and peaceful assembly. It is generally used by activists when all other means, such as the law, general advocacy, and other kinds of direct action have been exhausted. It has been used historically and successfully in campaigns against fracking, mining, and unsustainable forestry practices, but is risky for the individuals involved and, depending on the interpretation of local law, can involve many different forms of action.

Participating in and coordinating a civil disobedience campaign requires an understanding of local laws, thoughtful consideration given to your goals and tactics, and commitment to diversity and inclusion. Charities like Nature Nova Scotia do not participate in civil disobedience because we are bound by charity law in Canada. With the passing of the misleading “Protecting Nova Scotians” Bill in late 2025, it is now unclear what kinds of direct action might also constitute civil disobedience, or a violation of provincial law. Many kinds of protest activity, for example, are protected by the Canadian constitution, adding additional confusion to the situation facing nature in Nova Scotia. The “Protecting Nova Scotians” law seems to allow for the removal of research camps and equipment in addition to protest infrastructure, limiting the ability of researchers like us to survey working lands for species at risk, old forests, and other areas of conservation concern. Nature Nova Scotia stands in solidarity with those exercising their constitutional rights, rejects the strategic villainizing of scientists and concerned citizens by our government, and will continue to operate our projects on public lands as long as we are able.

Taking meaningful action for nature requires each of us to analyze our individual activism goals, risks, and potential approaches. Learn more at:

Learn more about civil disobedience action from the experiences of Amnesty International.

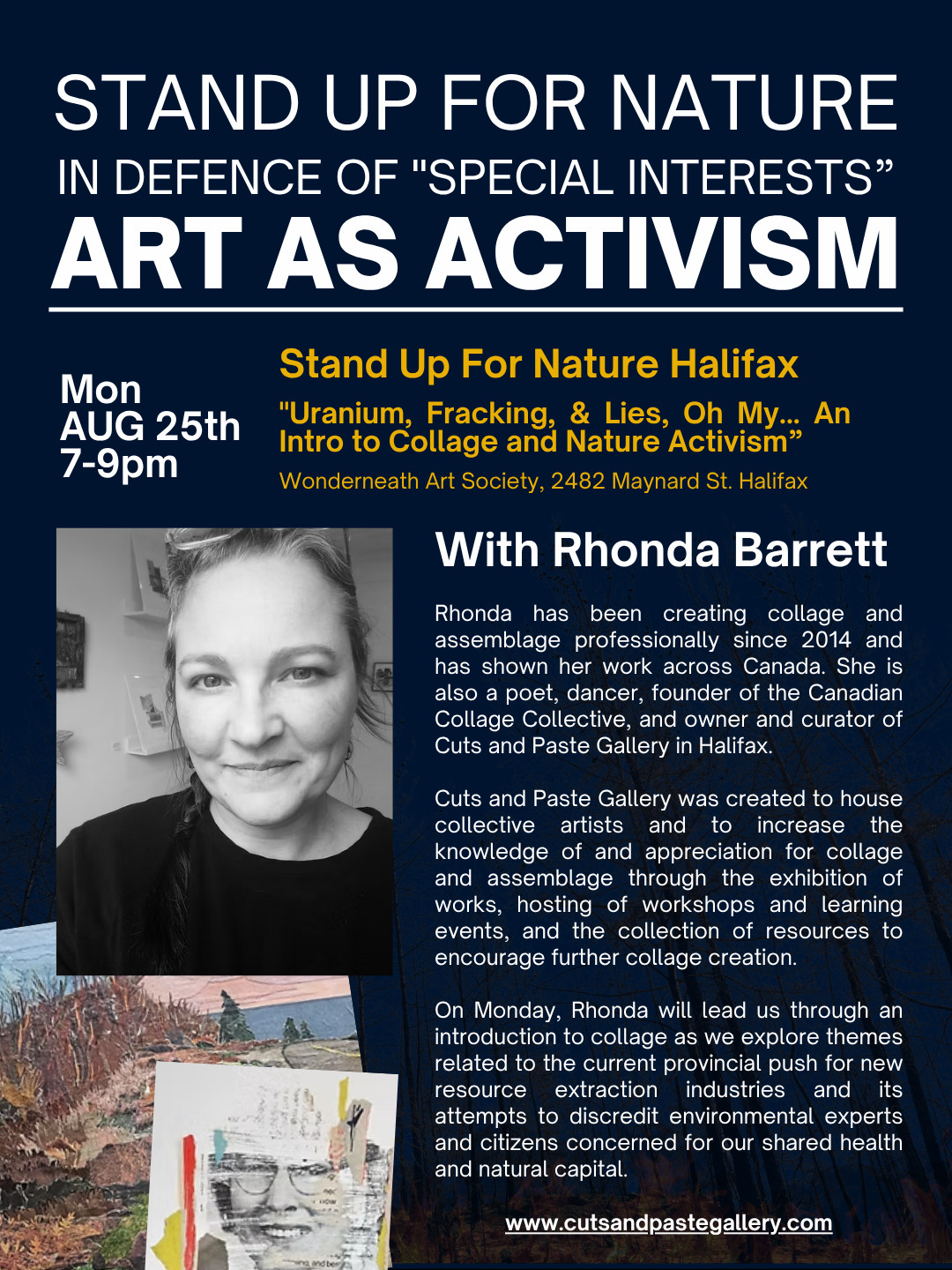

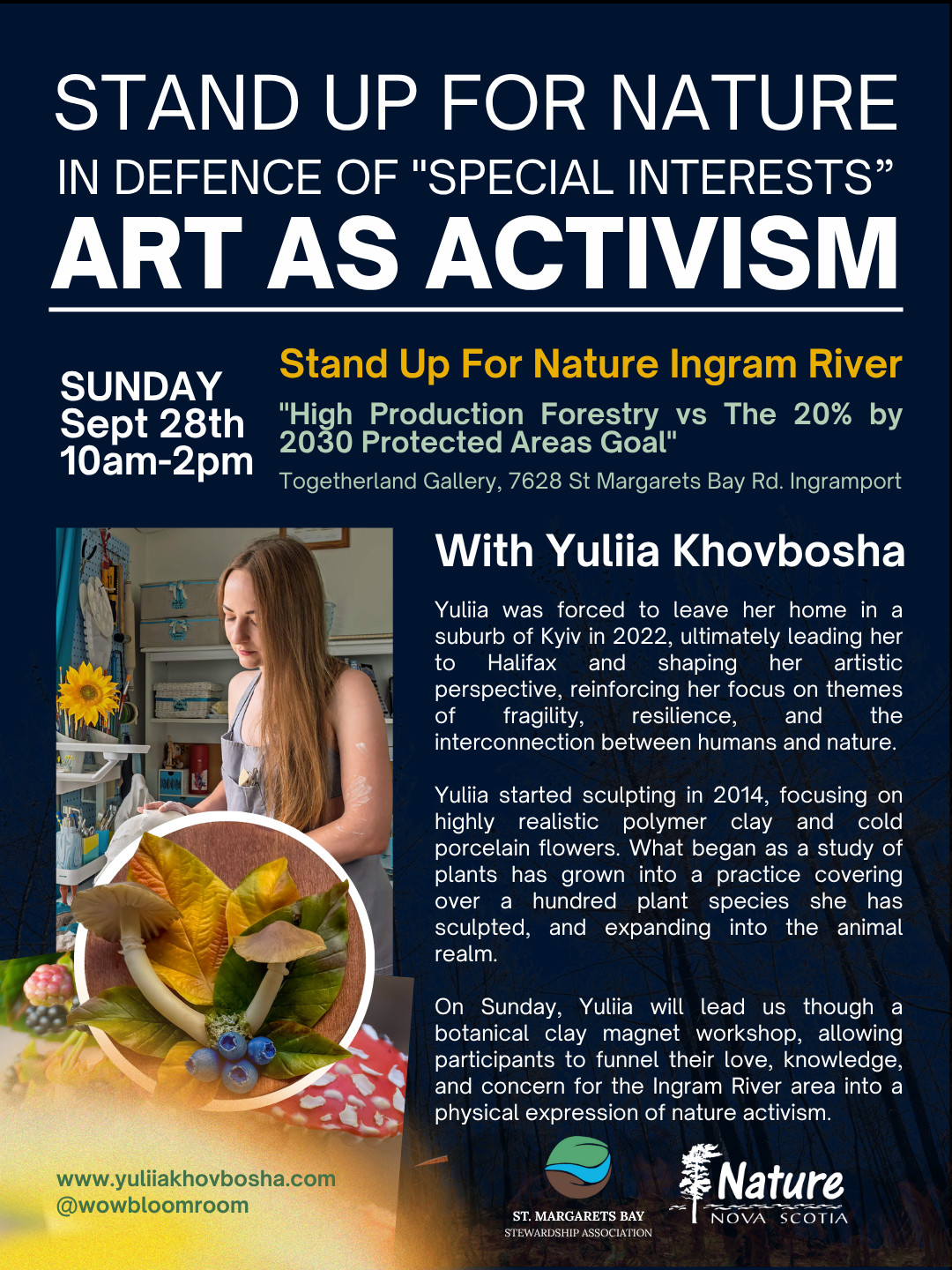

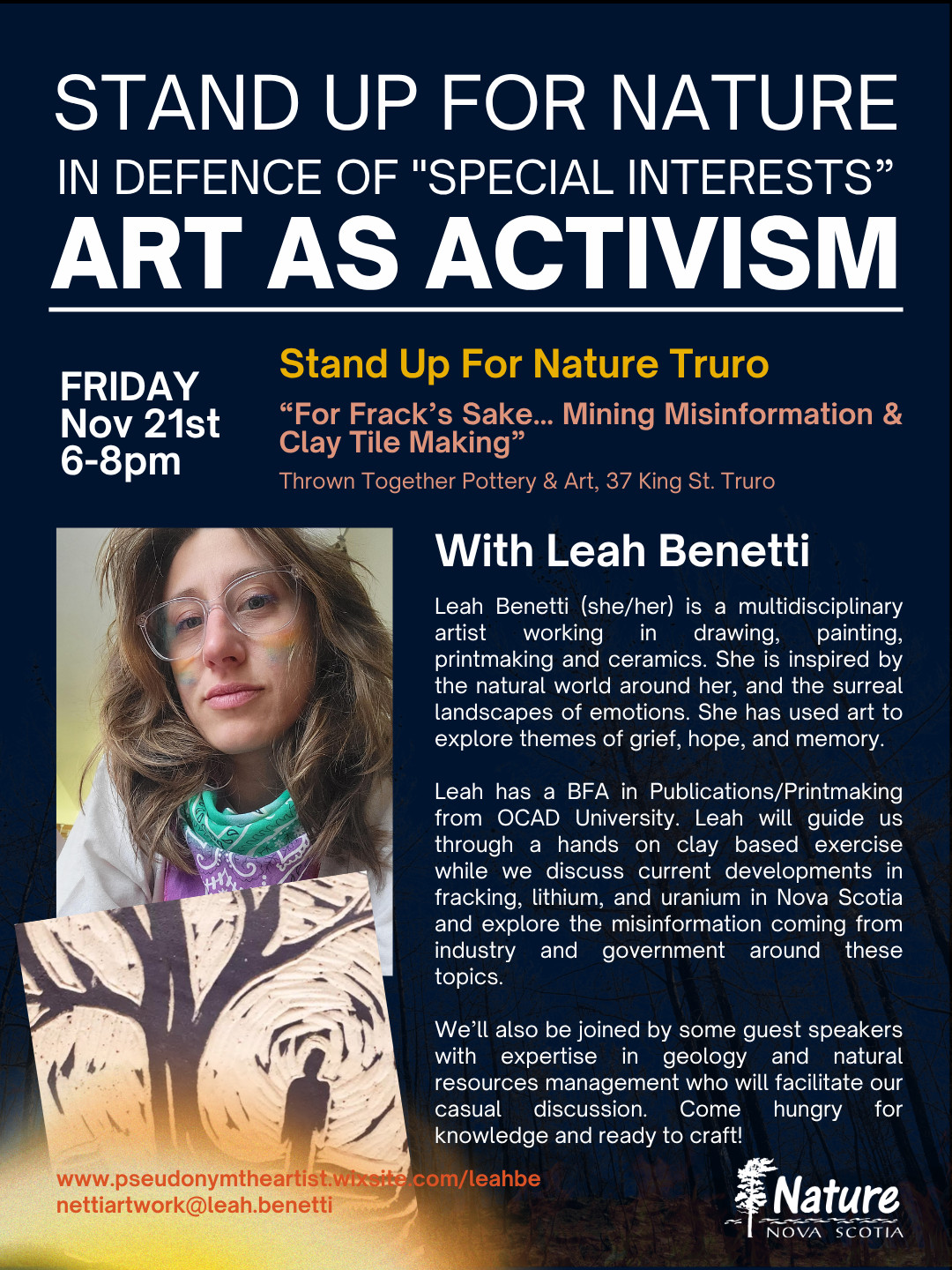

Want to take action while being social? Why not try out a new art at one of our Stand Up for Nature events!?

Help Us Reach More Nova Scotians

We are not alone. As part of our response, Nature Nova Scotia is leaning on the lessons of other jurisdictions who fought and won these battles before us. Working together, fighting the division the provincial government has sewn, we can save Nova Scotia.

We are organizing events where you can learn more about these issues, take group action, and take a stand for nature and democracy. Stay in the know by signing up for our e-newsletter, following us on social media, and checking back regularly. If you can, make a donation to support our work.